go straight to examples

Where a sea current flows along a coast, tides move beach sediment – sand, shingle, cobbles, rocks – in the same general direction by a process known as longshore drift.

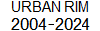

Any obstacle to longshore drift will have an affect on local sediment distribution. Groynes are widely used as a means of protecting the cliff line from coastal erosion. By design, a groyne traps and retains sediment at a particular location, in order to minimise wave action. However, the installation increases erosion elsewhere.

Shortly after a defensive structure is put in place, a section of cliff immediately downdrift of the work begins to erode at an increased rate, often dramatically. The resulting indentation develops a characteristic shape described as crenulate (from the Latin word for notch), which eventually extends some distance along the coast. Part of the embayment process attempts to creep behind or outflank the defence.

In time, the rate of loss will stabilise as the system adjusts to a position of equilibrium, or pattern of erosion similar to the coast in general, though the distinctive crenulate indentation remains.

The phenomenon of crenulate bay formation is increasingly referred to as the terminal groyne effect (TGE) or syndrome (TGS). ‘Terminal’ in this sense means the last of what might be a series of groynes in a groyne field.

It is not necessary for a groyne as such to be present. A seawall may result in increased downdrift erosion when reflected wave energy removes sediment. For convenience, the phrase terminal groyne effect is suggested for use with any detrimental interruption to longshore drift, though the term ‘end effects’ is sometimes used where there is no cross-beach element.

Various mathematical models are proposed to explain the development and planform of a crenulate bay – see references.

in detail

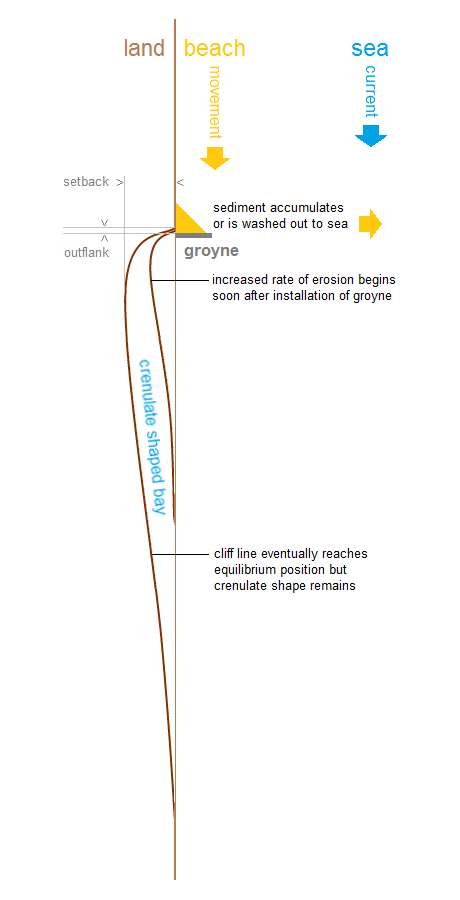

To take a closer look at the consequences of impeding longshore drift, consider first a beach with no barrier.

Wave A approaches the shore at an angle. It breaks, and water runs up the beach (swash). Under the influence of gravity, the water returns to the body of the sea by the most direct route (backwash). Some water may seep into the beach (percolation).

Because backwash typically possesses less energy than swash and cannot sustain the sediment load, a quantity of the material brought by the wave is deposited.

The swash of subsequent wave B runs across the sediment dropped in backwash A and adds to wave B’s load, part of which is released during backwash B.

As the action is repeated, wave after wave, tide after tide, material is progessively transported, or drifted, along the shore – longshore drift.

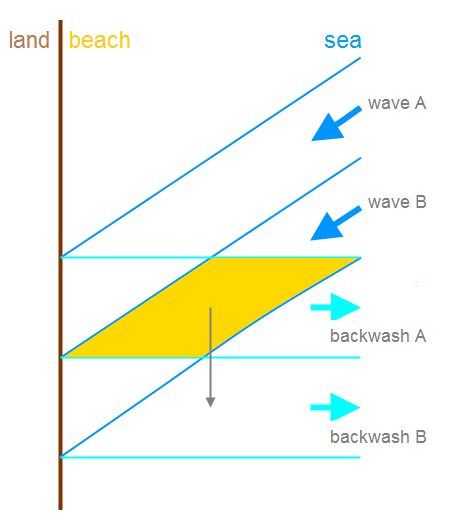

The insertion of a groyne has two impacts.

Wave C represents the last complete cycle that is possible updrift of the groyne. Some of the sediment carried by wave D is deposited in the same backwash path as that of wave C, and the beach cover gradually accumulates (accretion).

Backwashed material does not necessarily round the groyne but continues out to sea.

Downdrift of the groyne, wave E is required to flood a greater area. Sediment transported by wave E is insufficient to balance removal by drainage, marked as backwash E. Beach level is lowered, and the cliff near the groyne is exposed to greater high tide erosion.

More complex water movement, such as circulation, is possible especially in the case of larger structures.

East Yorkshire

Some prime examples of the terminal groyne effect are to be found along the coast of the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Bordering the North Sea, where the current flows north to south, the cliffs are formed from unconsolidated glacial tills. These soft clays allow processes of coastal erosion to be rapid and therefore observable over relatively short periods of time. For background, see some basics.

A little over 16% of the distance [detail] has some type of construction to counter the sea. Since a proportion of the material that constitutes the cliffs is made up of sand and coarse particles, a major defence work not only disrupts longshore movement but cuts off a source of beach material.

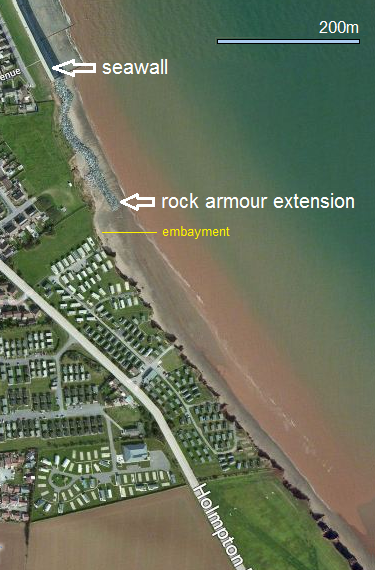

Withernsea south

The first substantial defences against the destructive power of the sea [video] were built at Withernsea during the 1870s. A number of extensions have followed.

Rock armour (‘rip-rap’) was introduced to prevent outflanking and protect fixed properties lying south-west of the seawall. Aerial imagery shows embayment, indicating an increased rate of erosion, beyond the extension added in 2005.

Evidence of earlier embayment episodes is visible behind the line of rock armour.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

[All above pictures 3 September 2012.]

The South Withernsea Coastal Defence Scheme was completed in December 2020, at a total cost of £7m.

A 400-metre extension of new rock was positioned and 100-metre length of existing rock realigned.

Seawall and rock now protect a continuous coastal length of 2.67 kilometres at Withernsea.

Report (15 February 2019)

The report comprises 347 pages (PDF). Page 5 (PDF page 14) shows predicted cliff erosion had the work not been undertaken. Appendix 6 B (PDF page 275) includes projected future cliff locations estimated using past erosion data.

East Riding of Yorkshire Council

Press release (17 December 2020, courtesy BAM)

Internet Geography

Information on the latest extension.

Withernsea south rock extensions

groyne field dimensions (spreadsheet)

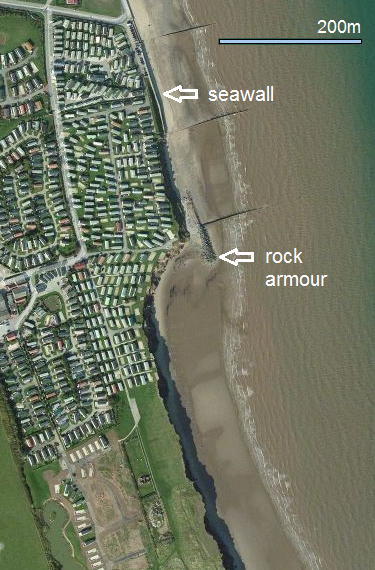

Hornsea south

A pair of groynes to help resist the sea at Hornsea were erected in 1869. These lasted six years. By 1890, protection consisted of seven groynes. Signs of consequential downdrift erosion were noted at the time.

Following a destructive storm in 1906, a substantial seawall was constructed, which has been extended on occasions since.

Beyond the southern end of the seawall, a cliff-parallel limb of rock armour was installed in 1977 to address the problem of outflanking downdrift of the terminal element of the Hornsea groyne field. There is also a gabion, or ‘rock cage’.

The arrangement is visible in the aerial picture as a T-shape, purposely separated from the seawall so that beach sediment may pass behind the structure.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Internet Geography

Presentation and drone imagery (2022).

groyne field dimensions (spreadsheet)

Mappleton

The village of Mappleton is where the B1242 coastal road runs close to the cliff line.

As early as the eighteenth century there was an awareness of how erosion was advancing on the village. In 1786 the church was measured to be 630 yards (576 metres) from the cliff. By 1990, the distance was 223 metres. The figures produce an average loss of 1.73 metres per year.

To protect both village and road, in 1991 a major defence scheme incorporating a prominent L-shape (that is, cliff-perpendicular and cliff-parallel) rock armour arrangement was constructed at an approximate cost of £2m.

Prior to the work, the rate of retreat along this section of coast was essentially the same for all points.

The aerial picture indicates that sediment has been retained north of the defence structure to create a beach more able to withstand wave erosion of the cliffs.

South of the structure, the terminal groyne effect has left its crenulate imprint on the coastline.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Mappleton gallery

Internet Geography

Presentation and drone imagery (2022).

Lands Tribunal (1999)

Decision regarding claim for compensation for loss of land south of Mappleton (Earle, Grange Farm, Cowden). The document comprises 56 pages (PDF), with a summary at p50.

Barmston

At Barmston, there are two examples of the terminal groyne effect.

Opposite the end of Sands Lane, a mass of recycled anti-tank blocks and other wartime remnants was installed around 1978. The concrete barrier offers some protection to the Barmston Beach holiday park.

About 750 metres to the south, Barmston Main Drain collects water from the land and discharges it through an outfall pipe into the sea. The cover has been in existence since the mid-1970s.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

[All pictures 23 November 2012 except where otherwise captioned.]

Barmston gallery

Ulrome and Skipsea

The map is from 2011. It shows two more examples of the terminal groyne effect, at Ulrome and Skipsea.

From the early 1990s a privately built and maintained seawall was a dominant feature at Galleon Beach, Ulrome. A ‘plug’ revetment was later installed to protect a property about 200 metres to the south at Skipsea. The construction at Ulrome was prone to repeated damage from the waves, especially at the southern end.

Ulrome and Skipsea defences were demolished and all material removed in spring 2015.

Ulrome gallery

Skipsea gallery

Green Lane, Skipsea

Easington

When the North Sea gas terminal at Easington was opened in March 1967 the belief was that the useful life of the installation would be over before coastal erosion became an imminent threat.

Gas reserves proved greater than first expected and a revised duration for the facility meant that protection was necessary. A kilometre long revetment using over 130,000 tons of rock was constructed in 1999, at a total cost of £6.6m.

The design stage of Easington gas terminal defences had to consider two nearby Sites of Special Scientific Interest. To the north lies Dimlington High Land and to the south are the Easington lagoons.

In view of the sensitivity of the near environment, planning permission for the revetment was granted to 2020, with the condition that if the facility was no longer in use, the rocks were to be removed. At 2020, and operations ongoing, permission was extended to 2045.

There is no cross-beach component to the configuration. The boulders lie at the base of an artificially profiled bank-like cliff which is covered by mesh, and vegetated. Beach sediment is able to pass freely along the defenced section.

Both ends of the revetment are rounded into the cliff behind tapered extensions in order to reduce outflanking.

![Easington defences [16/04/14] Easington defences [16/04/14]](images/Easington-defences-30912-776x582.png)

![Easington defences [01/06/17] Easington defences [01/06/17]](images/Easington-defences-203-776x582.jpg)

Terminal groyne effect on the scale of other defence structures on the East Yorkshire coast is not manifest at Easington.

Monitoring south of the revetment indicates some increase in the rate of cliff loss but a crenulate bay as would be characteristic of the full TGE process is so far absent.

[Centre pictures 16 April 2014 and 1 June 2017.]minor examples

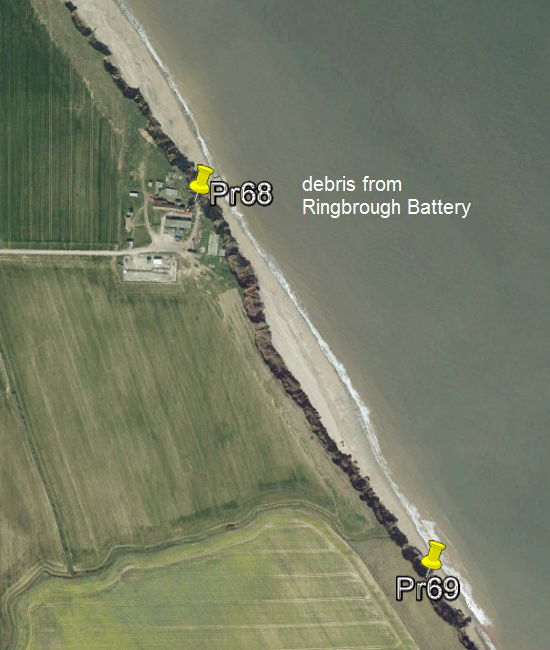

Sensitivity to the terminal groyne effect is such that even comparatively small interruptions to the movement of sediment can leave a tell-tale imprint in the cliff line.

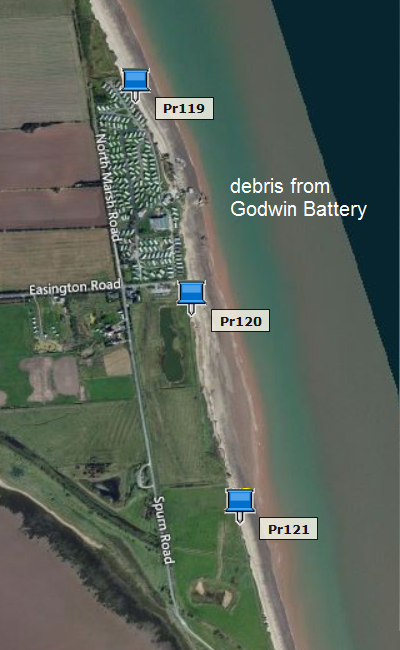

Along the Holderness coast, two wartime defence installations are reduced to debris on the beach.

Although remnants are best seen at beach level, their impact in geomorphological terms is clearer from above.

On the images, monitoring profile markers provide scale – intervals represent approximately 500 metres.

The Google Earth image from 2007 shows cliff setback south of beach debris at Ringbrough. Three years later, the observation tower (below the point of pin Pr68) tumbled over the cliff. More recently, the entire site was cleared.

Godwin Battery at Kilnsea is mostly gone.

Ringbrough gallery

Kilnsea gallery

top

references for this page

Page prepared by Brian Williams in August 2013. Last change December 2020.